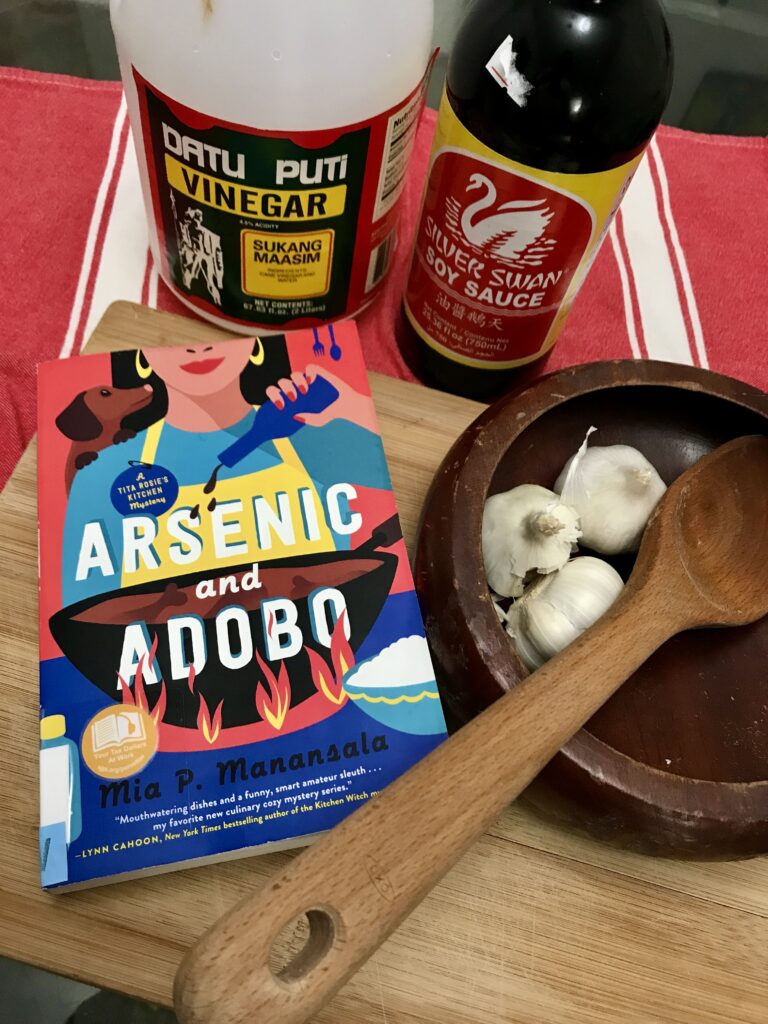

I was excited to read “Arsenic and Adobo” by Mia Manansala, a Filipino-American in Chicago. This year’s book trends show that US publishers have actively sought non-white, Asian, and female writers—authors historically ignored in the past.

I grew up on Filipino food and wanted to see my culture depicted in a book. I am also a murder mystery fan of Agatha Christie and Arthur Conan Doyle so I thought this would be the best of two faves!

As a debut novel, this cozy murder mystery is lighthearted with short chapters. But the author seemed too self-conscious in representing Filipino dishes and her culinary skills that it sounded like a cultural documentary with unneeded explanations.

On ube, “Oo-beh. It’s like a mild sweet potato that we use for desserts in the Philippines.”

It was hard to finish because it kept committing basic writing mistakes: there was no real emotion, the characters weren’t catchy, the dialogue wasn’t distinct, and there were many repetitions (Lila’s first love was murdered, overpriced college, she’s the family’s Hail Mary)—we get it!

The dialogue was sometimes unnatural because the Filipino characters translated their Tagalog words into English, “Tama na, that’s enough.” No one talks like that with fellow native speakers.

It was also weird that the protagonist kept eating under any circumstance. She’d come from a heavy meal, then meet up for merienda, then go home for snacks. Directly after a murder, they served sweets and drinks in the crime scene instead of going home!

The narrator-protagonist sounds like she’s performing for an American audience who has never met an Asian or Filipino. She seems to prioritize depicting Filipino culture over writing an engaging plot. Instead, she should have just focused on mystery readers regardless of race or country.

Christie and Doyle are English but they have fans worldwide. Culture always seeps out of stories anyway, it’s inherent in setting. So writers don’t need to make a big deal out of it that it takes away from the plot.

In the all-time favorite “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd”, Christie spent a whole chapter on mahjong as the characters discussed the murder suspects and their motives. It moved the story along because it summarized the clues and built suspense towards the final reveal. Christie doesn’t bother with cultural explanations on what mahjong is or what each tile means. She just wrote the characters playing as they would in real life.

It’s a primary rule in fiction that the main character should be likeable or at least compelling. But that’s hard to to do because readers come with preconceived notions and expectations. Readers love a hero they can identify with and care for. But first, the characters have to be believable.

The protagonist Lila is hard to pin down. At first she’s cute and flippant, she sounds like a blogger. She doesn’t react to the murder case against her with enough gravity as she casually goes from scene to scene just like any other day. This doesn’t make sense because when I practiced litigation, many defendants were found guilty even if they were innocent. Lila should’ve been anxious about her possible imprisonment, or at least shamed by the stigma of being a suspect. It would’ve been gossiped within the family.

The lawyer Amir also doesn’t seem to have a real legal career. It doesn’t specify what type of law he specializes in but he seems available at a moment’s notice to come to Lila’s aid. Lawyers are paid hourly so their days are solidly booked with client meetings, court appearances, research, and pleadings. They don’t have time to just pop in at any time of the day or night. Amir needs over 40 billable hours a week to earn well. He is losing money for every unpaid appearance he is making for Lila and her family.

Also, at odd moments, Lila suddenly cries when you don’t feel any emotion or tension behind it. No proper foundation was established for her reactions or actions, even for her past decisions. Why did she suddenly leave her boyfriend and town? Why can’t she commit to a business with her best friend? Other characters keep telling her, “Get over yourself.” What does that mean? Is Lila self-absorbed?

Lila keeps mentioning her overpriced education, but she doesn’t seem rational or focused. What does she really want to do with her life?

It was also annoying when she acted coy and ignorant of all the male attention she got simultaneously. Even when her aunts confronted her about it, she played dumb and brushed it off. Why isn’t she thrilled or at least honest about it?

As for the aunts and lola, it was hard to follow who was saying what. They seemed interchangeable. Maybe just stick to one aunt? Same confusion with the cousins. It was unclear what Lila’s conflict was with any of the other characters she has a sour past with, but it didn’t matter because none of it added to the story. Neither did it build enough drama to keep the reader’s interest.

It’s a lot, but no writer is immune from criticism. Master of mystery Agatha Christie wrote several duds after she was established late in her career.

There is a sequel “Homicide and Halo-Halo” with a preview of the first chapter at the end of the book. So far, the descriptions don’t move the story along, but I hope Mia heeds the readers’ and reviewers’ feedback so her next book captures the heart of various mystery readers everywhere.