Is there a looming electricity shortage, what experts call an energy crisis?

Well, it seems. The brownouts that swept the main island of Luzon on May 31 to June 2 are the precursor of things to come—power shortages equivalent to brownouts of four to eight hours a day. The power deficit could be worse than what authorities are willing to admit.

On May 31, 2021, there was a shortage of 1,752 megawatts (MW), on June 1 2,068 MW, and on June 2, 2,068 MW.

Four generators, with combined capacity of 1,579 MW, were shut down. Another two, old or derated plants, with total capacity of 489 MW, also went off line. Peak demand in those three days was supposed to be 11,841 MW. And supply was supposed to be 12,777. Instead, there was a shortage of between 2,068 MW (Department of Energy estimates) and 4,000 MW (private sector estimates).

NGCP blamed

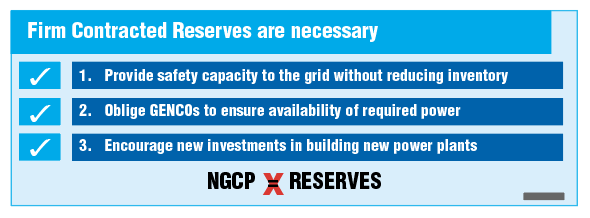

The DOE blames the privately-owned and managed transmission monopoly, National Grid Corporation of the Philippines (NGCP) for the outages. NGCP has not complied with its mandate to purchase so-called ancillary services (AS) – extra electricity supply to cover shortages, whether anticipated or accidental, as it happened during May 31, 2021-June 2, 2021.

NGCP probably thought buying AS was unnecessary. There was supposed to be enough supply during those days (May 31, 2021-June 2, 2021).

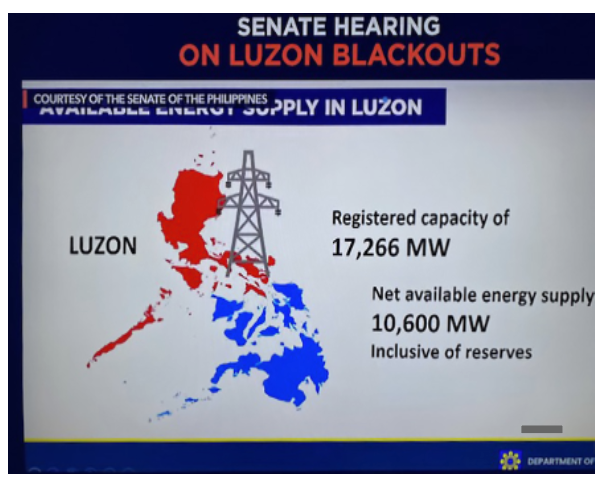

Energy Secretary Alfonso G. Cusi himself says available power capacity was 17,000 MW and peak demand was only 11,000 MW. “We have something like 6,000 MW excess supplies,” he told a Senate Energy Committee hearing on June 10, 2021.

What DOE did not anticipate was two major power plants suddenly shut down. Plus a number of power plants, with combined capacity of 4,000 MW, were de-rated. Why did these two events happen on the same days and at the same time? The DOE is investigating why.

Meantime, rotational brownouts occurred. High-priced electricity (the second highest in the world) is cheaper than having no electricity.

NGCP did not buy enough power reserves from the power generating companies to cover any shortages.

NGCP’s business

Grid operator NGCP maintains its main business is to transmit electricity, just like a tollway company which maintains an expressway to let vehicles pass thru. It is not its business to buy vehicles if there are not enough vehicles using the highway.

But the DOE counters that there are plenty of vehicles and that it is NGCP’s business to build more highways to accommodate more vehicles.

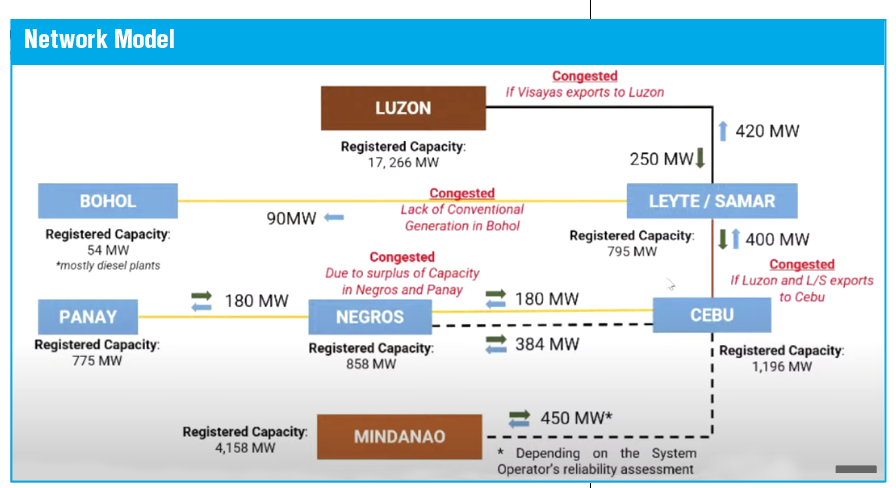

DOE says NGCP has been remiss in not building more transmission lines. While there is a shortage of electricity on the main island of Luzon, there are more than enough supplies in the Visayas and Mindanao. This excess electricity could be pumped into Luzon were there enough transmission lines, which is the business of NGCP.

Besides, being a monopoly NGCP has been raking in profits, more profits than they should have had. NGCP bought the transmission business from the government with a concession fee of only P168 billion. Yet, it has collected more than P209 billion in dividends.

Also, says Senator Risa Hontiveros, the weighted average cost of capital of NGCP, which it uses as a base to price its service, is two to seven times higher than the WACC of similar transmission companies in ASEAN.

Return NGCP to the government

Hontiveros notes that NGCP, supposedly a private company, is partly owned by the State Grid Corporation of China, “and has been blatantly disregarding Philippine government policies and standards.” The opposition senator wants the country’s grid system be returned to the control of the government.

“Taking back control of our main power grid system requires a system of strict oversight by the state. The individuals to take charge and become system operators should have a proven track record of integrity, competence and experience in running a complex system operation securely and efficiently. The end goal of which is to deliver reliable, stable and affordable electricity to all Filipinos,” Hontiveros argues.

Brownouts could have been worse

Were it not for the pandemic, the brownouts would have occurred as early as summer of 2020. The pandemic shut down 70% of factories and offices resulting in lower demand for electricity.

This year, with the vaccination rollout and lessening of restrictions on mobility, normal demand for power is gradually returning to pre-COVID levels. But supply has not been there.

According to officials of NGCP, installed power generation capacity should have been 24,000 megawatts by now.

But only 12,000 megawatts are installed, half of a more realistic demand for power. And 70% of existing generation plants are 16 years or older. Only one-fourth are five years or younger.

Old plants mean they are not as reliable as they used to, with rated capacity lower than claimed, and are expensive to maintain.

What to do then?

NGCP suggests more power plants should be built, an average of 1,600 MW per year over the last 15 years, or 24,000 by today. Instead, only less than half of that were built, leaving a possible shortage of 12,000 MW.

The Philippine Independent Power Producers Association (PIPPA) complains that it is so difficult and expensive to put up new power plants. There are many restrictions and many requirements. Red tape, in other words.

Cusi insists the problems is with NGCP. “Its transmission projects have been delayed by one year to nine years,” he told the Senate Energy committee hearing on June 10. Excess power is stranded in Mindanao, he said, as well as in Negros, and even in Zambales, in Luzon itself. These power supplies cannot be fed to the Luzon system “because of congested or uncompleted transmission lines.”

No reserves at all

“It is clear in NGCP’s concession that they must contract reserves,” the Energy chief points out. He recalls that as early as 2016, when the Duterte administration took over, he was already looking for these reserves to be contracted by NGCP. “There is no reserve,” he winces.

“NGCP’s compliance to buy reserves was only on paper,” Cusi complains. “It was like having a spare tire, but the spare tire had no air in it.” “I cannot understand why NGCP does not comply with its concession requirement to contract reserves,” says the Energy chief.

In retort, NGCP says it doesn’t want to contract firm reserves because doing so would increase the cost of power. “We cannot add any more burden to consumers during this pandemic,” explains an NGCP spokesman, Atty. Mutya Alabanza.

For her part, Senator Imee Marcos wonders:

“Is it time to revisit the reasons why we privatized Napocor in 2001? Are these arguments therefore all invalid today? The question also arises if the supply of reserves for summer is the issue, will the entry of government into power generation be the answer? We know how incompetent government was in the past. And are we saying that government will be much, much better today?”

Further, “what is the direction of DOE if we revoke the franchise of NGCP which, as we all know, is well within the legislative mandate? Does DOE truly believe that government can operate the grid long-term which in turn will need the amendment of the EPIRA?,” Senator Marcos has asked DOE’s Cusi.

How the system works

Richard Nethercott, president and CEO of the Independent Electricity Market Operator of the Philippines (IEMOP), explains how the system of reserves works:

“We have in the market registered capacity. Because of the Must-Offer Rule, all plants must make that registered capacity available. Our registered capacity is 17,266 megawatts.”

“Peak demand is projected for 2021 is 11,841. Total reserve requirement based on that peak demand requirement is 1,789 megawatts. Therefore, the net excess capacity is 3,636 megawatts.”

Where do the 3,636 MW go? “These are plants hit by outages, forced outages, and sometimes, de-ratings. De-ratings can be natural and operational. Natural de-rating happens during summer, and it hits the hydro, wind and sometimes, mid-merit plants, and peaking plants.”

The reserve requirement, under the rules and under the law, is a responsibility of the system operator (NGCP). There must always be sufficient supply of electricity, with reserves on top of it. But is sufficient supply always available? No. That is the mystery.

Senate Energy Committee Chair Sen. Sherwin Gatchalian explains the consequences of brownouts:

“No. (1), the vaccination rollout; No. (2), the work-from-homes; No.(3),education and a lot more. We are trying to revive our economy. We just extended our—or reduced our curfew hours. Meaning, we want businesses to thrive. But if there is no electricity, then how do we revive our economy? But as we stand right now, there seems to be no certainty.”

Senator Hontiveros adds another complication: “We are going to have an election next year. We cannot afford brownouts.”

Concludes Senator Gatchalian:

“The possibility of brownouts is there, and we just need to prepare. We need to prepare our LGUs, our selves. Right now, I am not getting a direct answer on what are the contingency measures.”

“We call on the DOE to convene a task force to address these imminent brownouts. We need to take this seriously. Whether it will happen or not, that’s beside the point, but the data is showing that it might happen; the possibility is high. So, let’s take the conservative route, and I urge the DOE to already convene their preventive task force to come up with a plan.

“We have to take this seriously. If it doesn’t happen, then well and good, at least we can rest at night. But if it happens, then we have a very big problem.”

READ FULL ARTICLE HERE: