By Tony Lopez

Our central bank governors have a sense of humor. It refers at times to their women, I mean, their wives.

When newly installed Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) governor, the taciturn with a wry smile Ph.D. economist (Stanford), Eli Remolona met banking industry biggies for the first time during the BSP’s 30th anniversary July 28, 2023, he spiced his brief 800-word speech with a joke.

Asked by Bloomberg, “Governor, when you’re not thinking about monetary policy, what do you think about?”, he related, “The right answer, of course, was, ‘I think about my lovely wife!’,’ to the stiff crowd’s delight, and Remolona added, quickly:

“But being the central banking nerd that I am, I said instead, ‘When I’m not thinking about monetary policy, I think about banking supervision and the payments system!’.”

When Remolona took over as the seventh BSP governor and his predecessor bade farewell to his BSP colleagues after a year-long stint as governor, on July 3, 2023, the economist Philip Medalla intimated:

“Although they are not with us now—this is the secret of my happy marriage; my wife is often out of the country—I thank my family, especially my wife Pinky and our children.”

And referring to BSP Deputy Governor Chuchi Fonacier, chief of banking supervision, Philip said: “When there is a job to be done, send the woman. The banks understand that.”

So there, the time-honored success formula or the secret of self-confessed banking nerds – women, the wives (singular per man), and their female executives.

Why women?

Why women? Well, the first woman President Cory Aquino once said women, or wives, are better at handling finances than men.

After all, as house managers, they manage the most basic but most difficult to manage economic unit –the household.

There are 24 million households in the Philippines—nearly all managed by women; easily a third are managed, singlehandedly, by a woman, because the husband is away, an OFW, in some faraway land—or ship. Nowadays, the No. 1 concern of households is what bankers and economists call inflation – the rate of increase of prices of consumer goods surveyed by the state for its Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Of the 100 points of the CPI, easily, for most households, especially the poor, 50 points is food. Of those 50 points, 15 points is rice or cereal. So for every P100 of a household’s budget, P50 goes to food; of that P50, P15 goes to rice. And rice, unfortunately, is priced mainly at P50 per kilo. And even more unfortunately, rice will remain in short supply in the coming years.

A central banker basically tries to control or regulate three things – prices; interest rate or the cost of money; and payments or how money is transferred from one user to another, ala Gcash.

A housewife often has no control of these three things; she just complains. Often, she has no cash.

More often, she has no bank borrowings (because only less than half of adults have a bank account and it’s so difficult to get a bank loan); and most often, she does not understand the workings of the payments system. Just like me.

After the pandemic, Governor Remolona said the economy had “a surprisingly strong recovery.” “It was a recovery like no other,” he gushed, thanks, he said, to the banking system.

“Our banks maintained more than adequate levels of capital and remained flush with liquidity. This time, there was no need to repair balance sheets. I have said this before, and I’ll say it again. Unlike in previous crises, this time our banks were part of the solution rather than part of the problem.”

“Our immediate challenge,” Remolona conceded, is inflation.

“We were hit by an unusual confluence of supply shocks. We were hit, for example, by a spike in global prices of fertilizer – so not just food prices and not just oil prices. This was due, of course, to the sanctions on [shipping from] Belarus and Russia,” explained Remolona.

What did the BSP do? Instead of helping produce the food (as it used to do under the old 1949 Central Bank Act), it made more expensive the money that could be used to produce the food.

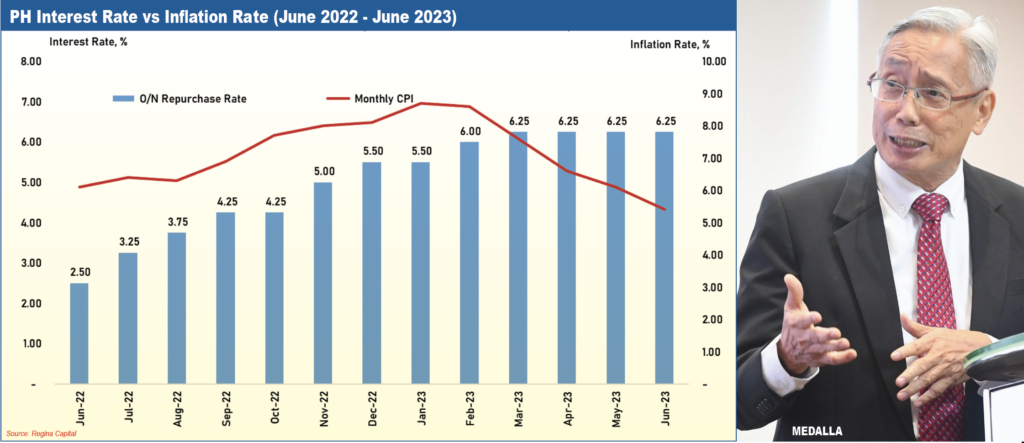

By raising interest rates by a cumulative 4.25 percentage points– .75 percentage-point under then BSP Governor Ben Diokno (now the finance secretary), and 3.5 percentage points under Governor Medalla.

So if money two years ago cost nothing or zero, it now costs 4.25%. That’s stiff and oppressive.

But the BSP people are happy. “Headline inflation seems to have peaked and looks to be on its way to our target range of 2 to 4%,” said Remolona.

Tantalizing fruits

“We’re beginning to see tantalizing fruits of our efforts.”

And Remolona et al are not done yet. “It’s too soon to declare victory. Core inflation remains high,” he told bankers last July 28. “There are still upside risks to inflation – for example, risks in the form of El Niño and further supply shocks. We will wait and see.”

One other benefit of high-interest rates was it stopped a rapid peso depreciation of up to P65 to $1 by some forecasts.

The peso appreciated, from a record low of P59 to $1 in October 2022 to P55.20 to $1 by June 30, 2023. A 6.4% peso appreciation means importing food became cheaper by 6.4%. And importing food is the only way to cover a 25% overall food shortage.

“Our more stable exchange rate helps us avoid excessive depreciation that may dislodge inflation expectations and add to inflationary pressures,” explained Medalla last July 3, 2023.

Tantalizing? Ask the housewives.