The demand for health care services is rising rapidly throughout Asia due to population growth, aging, and sustained economic development, and the Philippines is no exception.

With the best GDP growth in ASEAN for nearly five years and counting, the Philippines has been experiencing robust growth, and the private health care industry has been no exception, as witnessed by the rapid expansion of private health care facilities to service the growing middle class of the country.

However, there remain significant, widening gaps in the access to and quality of care between the private and government health care sectors for certain types of services that can be offered or provided compared to developed countries, including and especially for advanced technology imaging.

MRI, CT, and now PET/CT in more developed economies are indispensable cornerstones of the health care system. However, despite the technology being introduced over 30 years ago, this basic modern health care technology remains inaccessible to the majority of people of developing countries. Why?

The answer lies in the current capitalist liberal world order, where the sales of high end medical devices is very much one of the key industries that large western multinational corporations act in accordance with the political and economic agendas of their governments.

By keeping the pricing and technology exorbitantly expensive, the existing multinational manufacturers who control this industry have kept the cost of this vital humanitarian medical technology prohibitively high and out of reach for greater than 80% of patients in the developing countries of the world.

Currently in the Philippines, only the expensive private hospitals and top tier academic teaching public hospitals in major cities can afford advanced technology imaging, causing severe overcrowding and inadequate access to care. Hence, at one major academic medical center in the US, there often are more MRI scanners than in all of Mindanao, whose population now exceeds 30 million.

New breakthroughs in scintillating crystal and magnetic imaging coil technology have allowed several innovative companies in China to develop MRI, CT, and PET/CT scanners that approach the quality of the latest multinational technology but at a small fraction of the cost.

Though not at the level of the GE/Philips/Toshiba scanners (collectively known as GPS), the Chinese made scanners are more than adequate for diagnostic of the great majority of conditions for orthopedic, neurologic, gastrointestinal, urologic, pulmonary, etc conditions.

With highly affordable pricing levels, access to this critical service can be created where there currently is none, benefitting millions of patients. Add to that China’s willingness to provide affordable financing thanks to the warming of ties under the current administration, and there is now an opportunity to dramatically change the healthcare landscape of the country.

The introduction of low cost, high technology imaging has been extremely disruptive to the China’s own domestic medical scanner market as well.

The multinationals have been forced to respond by lowering prices, offering lower cost models, or pushing refurbished scanners onto the market, all of which are still far more expensive than the Chinese counterparts.

That also does not include the multimillion dollar mandatory service contracts that the multinationals obligate their customers to, whereas the Chinese have very aggressive service and financing contract terms.

A telling recent experience was the acquisition of a refurbished CT scanner by Ospital ng Maynila in 2016, which was operational for only four months.

The bill the manufacturer wanted to charge the taxpayers of Manila to fix it? $450,000, almost double the cost of a new Chinese scanner, including service.

A counter argument often offered up from developed countries and their industrial captains (not just in health care) is that the market of developing countries such as Southeast Asia does not hold enough potential in order to justify the costs of bringing such a product to market.

Evidently China does not agree, and is rapidly pursuing the development of affordable, hi-tech medical products in many areas.

So what is the response of multinationals and their governments then – accuse China of intellectual property theft and enact punitive trade tariffs! Really now, is that acting in the interest of patient care without borders? Keeping affordable health care technology out of the hands of 80% of the world’s population?

Most importantly, in the current regional geopolitical context, the two countries of Philippines and China are undergoing a historical warming of ties and a major recalibration of their previously contentious diplomatic relationship that promises to bring significant benefit to both nations, let alone the entire region and global community.

Being familiar with industry and government on both sides, Dr. Mow has proposed to the Duterte administration a project to facilitate aid from China specifically for hospital upgrades and modernization for MRI and CT scanners, which was announced by the President at his press conference upon his return from the Boao Economic Summit in Hainan, China on April 13.

Total knee replacement: Relieving pain and restoring function

Since being introduced in the 1960s, Total Hip and Knee Replacement (THR and TKR) have evolved to be among the most common and most successful surgeries of modern medicine. Over three million joint replacements are done each year worldwide, and this number is increasing rapidly due to population growth and aging. In the United States alone, there are over 700,000 knee replacements per year, and close to one person out of every 100 persons over 65 have a joint replacement. Not only are people living longer, but they are living healthier, more active lives. Hence the demand for these procedures is growing, especially in the Asia Pacific region.

Knee and hip replacement technology continues to evolve and improve, as patients place more and more demands on the existing technologies. New materials are being introduced that are smoother, harder, and longer lasting, to allow patients to engage in as many normal activities as possible, for as long as possible. The technique of surgery and anesthesia also continue to be advanced, so the surgery is safer, less painful, and easier to recover from. Doctors also continue to improve their knowledge and skills worldwide, through continued research, education and collaboration.

Knee and hip replacement technology continues to evolve and improve, as patients place more and more demands on the existing technologies. New materials are being introduced that are smoother, harder, and longer lasting, to allow patients to engage in as many normal activities as possible, for as long as possible. The technique of surgery and anesthesia also continue to be advanced, so the surgery is safer, less painful, and easier to recover from. Doctors also continue to improve their knowledge and skills worldwide, through continued research, education and collaboration.

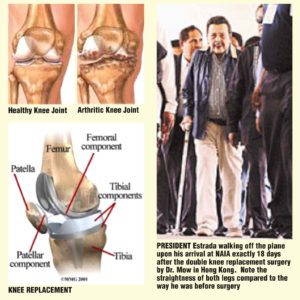

Former President and now Mayor of Manila Joseph Ejercito Estrada is a good example of a patient who was in dire need of knee replacement surgery, as prior to surgery he was at the point where every single step was causing him pain. He suffered from osteoarthritis of the knees, which affects up to 1 in 4 people worldwide by the age of 60. A normal knee joint has a cartilage coating on the ends of the bones, which normally is slippery smooth and moist, and acts like a Teflon surface or treads on a tire (see healthy knee joint diagram). Over time, due to aging, previous injury, or other causes, the cartilage thins out, or wears away completely, as it had in the former President’s case. When the knee is completely worn out, the leg may become angled and lose its flexibility, further causing the patient pain and disability (see arthritic knee joint diagram).

Once the knee is completely worn out, then knee replacement surgery is the only treatment that will reliably relieve the pain and restore the function. Total knee replacement is not a small surgery, and requires a stay of a few days the hospital. However, it is not as serious a surgery as something like a heart bypass or liver surgery. If the patient chooses to have the surgery, then the patient needs to have a thorough checkup to make sure there are no other major health issues to ensure the safety and outcome of the surgery.

The surgery itself is performed under anesthesia (usually spinal, where the patient’s body is numbed from the waist down) and typically takes 60-90 minutes. The knee joint is opened up from the front, polymer pad or shim is then snapped in place to act as the cushion and the knee (see knee replacement diagram) then stitched closed securely to finish the operation. Former President Estrada’s surgery lasted a little more than three hours total to complete the surgery for both of his knees.

The surgery itself is performed under anesthesia (usually spinal, where the patient’s body is numbed from the waist down) and typically takes 60-90 minutes. The knee joint is opened up from the front, polymer pad or shim is then snapped in place to act as the cushion and the knee (see knee replacement diagram) then stitched closed securely to finish the operation. Former President Estrada’s surgery lasted a little more than three hours total to complete the surgery for both of his knees.

After surgery, the patient usually stays in the hospital for a few days to make sure there are no problems and to start the rehabilitation. Exercises are started right away and it is important to get up and out of bed within 1-2 days to prevent blood clots, pneumonia, and other problems. Usually within a few days, the patient is able to walk with assistance well enough to return home with supervision. After being released from the hospital, the patient needs to continue doing exercises with physical therapy for another 1-2 months. The former President stayed in Hong Kong for 18 days after his surgery, and returned exactly on schedule as mandated by the Sandiganbayan. He was able to walk off the plane and jetway himself using only a cane.

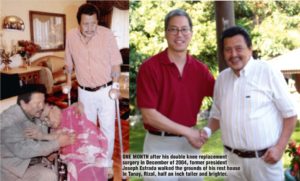

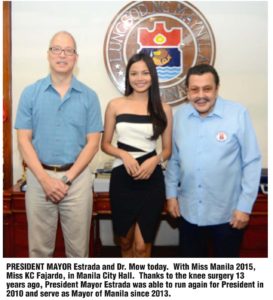

By three months after surgery, the patient is usually fully or near fully recovered, and may resume normal activities. The knee replacement of today is very sturdy and can do almost everything except for running, jumping, and high speed sports. The former President was able to return to a very normal life, including running for the highest office in 2010, and resuming his long and storied career as a civil servant as the Mayor of Manila in 2013, the office which he currently holds. He often states, “Dr. Mow’s knee surgery made me feel 30 years younger. In more ways than one!”

ERAP ON HIS FEET AGAIN

One month after his double knee replacement surgery in December of 2004, former president Joseph Estrada walked the grounds of his rest house in Tanay, Rizal, half an inch taller and brighter. Between breakfast and bedtime, he spent much of his time gardening, doing light exercises, praying, and reading the Bible, which were pretty much the only things he could do under house arrest at that time.

One month after his double knee replacement surgery in December of 2004, former president Joseph Estrada walked the grounds of his rest house in Tanay, Rizal, half an inch taller and brighter. Between breakfast and bedtime, he spent much of his time gardening, doing light exercises, praying, and reading the Bible, which were pretty much the only things he could do under house arrest at that time.

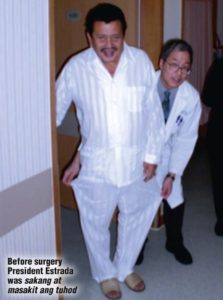

But for years before that, he was walking like a duck, waddling, bowlegged, because his knees bore the brunt of years of being arthritic. The bones of his knees were grinding together; the tissues around them severely inflamed.

His personal physician and then medical director of the San Juan Medical Center, Dr. Lorenzo Hocson, had to inject steroid and anesthetics into the actual knee joints—at the same time, prescribe analgesics for an enhanced effect—to bring at least a few days of relief from the pain.

His back was also troubling him greatly. He had several slipped discs at the lumbar level. And according to Dr. Hocson, Estrada’s gait, which was “very bad,” did not help any with this problem, serving to exacerbate the pain. The lower-back pain and the pain from arthritic knees combined to give birth to a different kind of pain.

For more than two years, President Estrada had been requesting the Sandiganbayan for permission to go to Hong Kong for double knee-replacement surgery for both knees by Dr. Christopher Mow. But his action resulted in inflicting pain on a more grand scale level, inflaming several raw nerve endings in the body politic of the Philippine nation at the time.

Ripples of anxiety washed over many who feared he would use it as an opportunity to walk away from legal and political entanglements, acquired primarily from two-and-a-half years of presidency, something that has become eerily recurrent in our recent history.

Ripples of anxiety washed over many who feared he would use it as an opportunity to walk away from legal and political entanglements, acquired primarily from two-and-a-half years of presidency, something that has become eerily recurrent in our recent history.

As history tells, the permission was ultimately granted, and on Dec. 26, 2004, former President Joseph Estrada boarded a flight with his family bound for Hong Kong to undergo the surgery to be performed by the American orthopedic surgeon from Stanford University, Dr. Christopher Mow. Of course, when he came back on Jan. 15, 2005, the exact deadline set by the Sandiganbayan, spurning further requests for an extended stay in Hong Kong, he walked all over these concerns—which either reassured these anxious people mightily or dashed their hopes for a vindication of their warnings.

Knee-deep in pain

On December 26, Estrada left for Hong Kong for surgery at the Hong Kong Adventist Hospital. Prior to this, of course, the outcry was deafening and the objections were vehement, creating one of the most contentious political standoffs of our nation that decade.

This was, perhaps, not surprising for someone like Estrada, who probably never had a scarcity of drama in his entire life, who was an action man all the way from being an actor, to mayor, to senator, to vice president, to president, and finally to political prisoner—at least, this is the image that most people have of him.

However, in this case, he could not just take in stride the opposition, because, literally, he could not.

He was knee-deep in osteoarthritis, a degenerative joint disease that attacks men and women equally, but men earlier because, very likely, of their more physically strenuous lifestyles.

Dr. Hocson and Dr. Mow surmised that Estrada’s knee and back problems probably originated in injuries sustained playing basketball and performing stunts during his younger years during his acting career.

“The osteoarthritis—we all feel started from what we call traumatic arthritis…due to injury,” Dr. Mow shared. He explained that it has been observed that most athletes or those who suffered from physical injuries are more prone to develop osteoarthritis earlier than those who have not been as physically active.

He was still a senator when the condition started to manifest but it was only during the campaign for the vice presidency that it started to really get bad, recalled Dr. Hocson.

And then for two years at Veterans Memorial Medical Center, where he was held following his impeachment in 2001, Estrada was not able to walk around much, not being allowed to, leading to much weight gain. The inactivity weakened his muscles, and the added weight meant more pressure on the joints.

Total knee replacement surgery

Regretfully, in all the rush and with all the pressure, they weren’t able to take pictures of or videotape the operation at all. At the very least, it could have served as proof that the knees were really as bad as Estrada maintained all along, despite the many certified medical affadavits provided to the Sandiganbayan by Dr. Mow and Dr. Hocson. However, the most important issue at the time was allowing Dr. Mow and his team to perform the surgery quickly and safely.

Regretfully, in all the rush and with all the pressure, they weren’t able to take pictures of or videotape the operation at all. At the very least, it could have served as proof that the knees were really as bad as Estrada maintained all along, despite the many certified medical affadavits provided to the Sandiganbayan by Dr. Mow and Dr. Hocson. However, the most important issue at the time was allowing Dr. Mow and his team to perform the surgery quickly and safely.

“We forgot at the time,” Dr. Hocson said ruefully, “with all the political and logistical problems that came up prior to the operation.”

Dr. Hocson was present with Dr. Mow during the operation on Dec. 31, 2004 and he saw how there was no cartilage at all about the knee joints. “The bone should be smooth [but] his bones were already scratched, like you filed [them] with sandpaper,” he reports.

When the each knee was opened, close to 100 cubic centimeters of inflamed fluid came out of each, and the tissues around had to be removed “because they were already useless.”

The three-and-a-half hour operation went smoothly. Bone and cartilage at the end of the thighbones and top of shinbones were removed and titanium implants were cemented into place to function as the new knee joints.

If he had not had this surgery, Estrada risked not being able to walk for the rest of his life.

Why Hong Kong?

This was the one of the top questions in everyone’s mind last December, probably second only to whether he was going to run as soon as he could. Most people jumped to conclusions, earning the ire of many.

This was the one of the top questions in everyone’s mind last December, probably second only to whether he was going to run as soon as he could. Most people jumped to conclusions, earning the ire of many.

But Dr. Hocson always stressed that “The expertise of our Filipino orthopedic surgeons was never a question.” But he qualified: “Wouldn’t you rather be operated on by a doctor that you have confidence in…you know…has treated you for many years and you had a good relationship with?”

And that doctor was Christopher Mow, who first consulted for Estrada in November of 1998. Dr. Mow had been recommended to the new elected President by then Congressman Baby Asistio and Senator Tito Sotto. A young rising star from Stanford University at the time, Dr. Mow had already treated several well known Filipino clients, including the late Governor of Bicol, Felix Fuentebella and several members of the Madrigal family.

Mow recalls that in November 1998, he had never been to the Philippines before, and the next thing he knew he was sitting across from the President alone in his private study in Malacanang. “I was so nervous,” Mow remembers. “But I quickly realized what a genuinely friendly and approachable person the President is. I was intent on my Professional duties and we got to know each other very quickly.”

Dr. Hocson confirmed many times that Dr. Mow could have operated in the Philippines at the time. But Dr. Mow himself was apprehensive about doing so, having been advised by the United States State Department that he could be arrested here if he refused the Sandiganbayan and Senate orders to testify regarding Estrada’s medical condition and treatment. Therefore Hong Kong was chosen as an alternative venue, given Dr. Mow’s familiarity with that territory and the world class facilities that were available there.

Walking on

Estrada was supposed to leave on Dec. 19, 2004 but deferred his departure so he could attend the funeral of his best friend Fernando Poe Jr., whose sudden death he took very badly.

Dr. Hocson, family, and friends were concerned that his emotional suffering might affect the outcome of the medical tests and surgery later. They talked to him but Estrada was determined. Dr. Hocson quoted Estrada: “I also had to think of myself. I have to get better to be able to continue and pursue what my good friend had started. Dr. Mow had also made a lot of preparations and the show had to go on.”

Dr. Hocson agreed. That was the chance he was given, he points out, “which [Estrada] had been wanting…been postponing for a number of years before and during his Presidency. Then he was forced to wait even longer after he was put at Veteran’s Hospital and house arrest”

On Jan. 15, 2005 Estrada came back to the country as intended. He was accompanied by Dr. Mow’s physical rehabilitation specialist from Hong Kong, who stayed for several weeks to work with their patient and instruct the local therapists on what stretching and muscle strengthening exercises Estrada should do.

“I’m just so glad that I can walk straight again. But what I’m most happy about is I no longer experience spasms of pain around my knee day in and day out. Before, I would actually hear my knees crackling when I walked and sometimes I would even wake up in the middle of the night because my knees were hurting so much. Sabi ko nga e baka sakit sa puso pa ang ikamatay ko,” jokes Erap in his own comedic way. “Now I can even dance again.”