Can new DepEd Secretary Sonny Angara do something? The hope is that he can. Or there is really no future for this country.

By Tony Lopez

Congratulations to Senator Juan Edgardo “Sonny” Angara. He is the new secretary of the Department of Education. On July 20, 2024, he succeeds Vice President Sara Duterte who resigned for personal reasons, unwelcome in President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr.’s cabinet.

Sonny inherits the biggest bureaucracy in the government, with close to one million teachers and a P715.2 billion budget for 2024 alone, a seven-fold increase in ten years.

MATATAG agenda

Under the 2025 national budget, DepEd has taken on a hugely ambitious mission—the so-called Matatag Agenda:

— MAke the curriculum relevant to produce competent and job-ready, active,

and responsible citizens;

— TAke steps to accelerate delivery of basic education facilities and services;

— TAke good care of learners by promoting learner well-being, inclusive education, and a positive learning environment; and

— Give support to teachers for them to teach better.

Specifically, DepEd will:

1. Strengthen and expand access to Early Childhood Education

2. Ensure access to learning resources

3. Accelerate the delivery of Basic Education Facilities

4. Develop and pursue globally competitive and inclusive Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) and higher education programs.

Plainly, the agenda is to improve the quality of public education — elementary and high school education. Today, that quality is one of the worst in the world.

Compared with their global peers, Filipino students are at least behind five and a half years behind in learning, despite being in the same grade or year in school.

In 2022, out of 81 countries that took global tests for competency in reading, math and science—and creativity. Filipino 15-year-olds were second to last or third from the last. We beat two or three countries much smaller and much poorer than us.

Attendance ratio ok, but quality bad

The Philippines is on par with countries with middle-income gross domestic product (GDP) per capita levels in school attendance, notes PIDS.

However, in terms of measures of learning, the country falls below potential. World Bank (2020) estimates a learning gap of 5.5 years when the expected years of schooling are adjusted for education quality while students are in school. (See Figure 3b, page 17)

This gap is larger than the Philippines’ neighbors.

Although the DepEd 2018 PISA National Report (2019) shows that senior high school students achieved significantly higher proficiency scores than junior high school students in all reading subscales and had Level 2 compared to Level 1 proficiency in math and science, the country’s estimated learning gap indicates that, in general, an average 18-year-old Filipino student learns less in school than his/her counterpart in comparator countries.

Per a 2022 World Bank report on global learning poverty, 9 in 10 Filipinos could not read and understand a simple age-appropriate text at age 10.

Is Sonny Angara up to the job?

Is Sonny Angara matatag or tough enough for the job?

Last time I was talking to him, Sunday night (June 30) at the Kalayaan Hall holding room for those attending the Concert at Malacañang Park as guests of the First Couple, genial Sonny was gung-on about being DepEd secretary. He knows its problems at heart. He is incensed at the poor quality of Filipino children’s education. He wants something done—fast and substantially.

Sonny has tremendous gravitas—basic education at Xavier School, bachelor of science in international relations, with honors, from London School of Economics; law degree from the University of the Philippines, and master of laws, at Harvard. He was also a law professor.

Sonny’s dad, the late Senate President Edgardo Angara inspired the setting up of two educational commissions to reform the Philippine educational system.

The latest one is the Congressional Commission on Education (EdCom2), after the results of the 2018 Program for International Students Assessment (PISA) came out.

The country’s 2018 PISA performance was dismal, to say the least, says EdCom2.

This prompted stakeholders and advocates to declare a crisis in Philippine education. Coupled with a pandemic that further exposed vulnerabilities in the education sector, the issue, already long-standing at that point, became even more pronounced. Alarm bells were heard loud and clear in our legislative halls, and the EdCom was convened. “Yes, there is an education crisis,” declared EdCom2 which formally convened in Jan. 23, 2023.

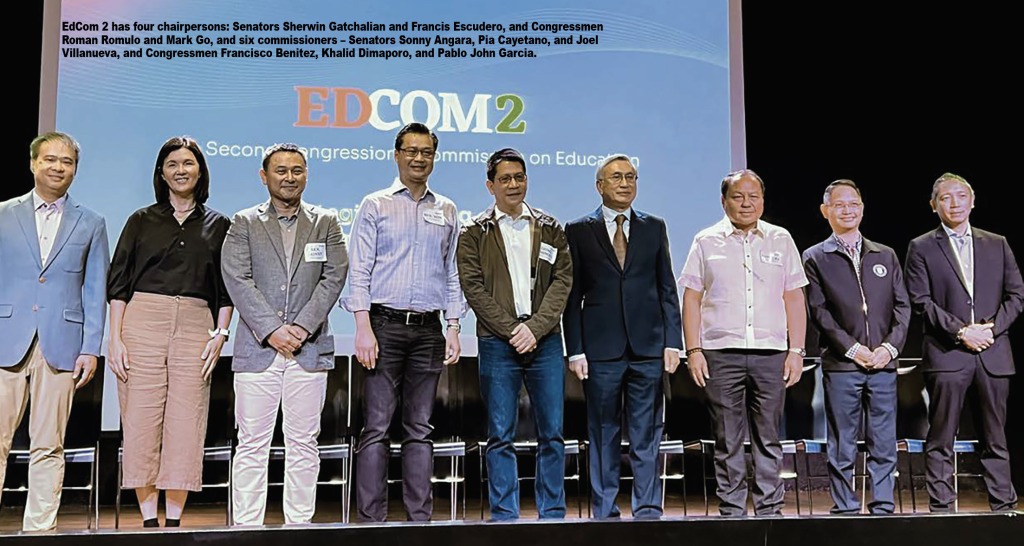

EdCom 2 has four chairpersons: Senators Sherwin Gatchalian and Francis Escudero, and Congressmen Roman Romulo and Mark Go, and six commissioners – Senators Sonny Angara, Pia Cayetano, and Joel Villanueva, and Congressmen Francisco Benitez, Khalid Dimaporo, and Pablo John Garcia.

In 2022 PISA test results, Philippine performance barely showed improvements. The scores remained dismal.

Education infrastructure bad

EdCom2 itself sees the whole Philippine education structure is rotten. There is no coordination among the various agencies involved in education.

Explains EdCom2 after its first year:

“A system is defined as ‘a regularly interacting or interdependent group of items forming a unified whole.’

“By this standard, the education system in the Philippines struggles to meet the criteria of a “system.” By the standards of the 1987 Constitution as well, it is short of ‘a complete, adequate, and integrated system of education.’

“Instead, agencies, bureaus, and offices have focused on their respective mandates and targets, often independent of one another.

“This is evident in the challenges uncovered by the Commission in its first year: from the fragmented implementation of ECCD interventions; the disjointed pathways in teacher development (from preservice to licensure, to hiring); the lack of education programs for critical education professionals; the absence of monitoring mechanisms, as well as the inequities reinforced by the Special Education Fund; and the ineffective coordination aggravated by the immoderate number of interagency bodies to which DepEd, CHED, and TESDA need to attend.

“This, amidst the ever-expanding mandates of the three agencies, despite their finite number of personnel.”

PIDS finds challenges

In 2023, the think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) reviewed EdCom2 and found a number of challenges.

In global competency tests in reading, math, and science, Filipino teeners among the lowest—the world—scores, far below those of their ASEAN peers, and below those of students with the same income class as the Philippines.

Per PIDS, the students’ low test scores correlate with:

1) The late start of formal schooling at Grade 1;

2) Lack of parental support and low models of aspirations;

3) Lack of resources in school, such as learning materials and classrooms;

4) Absence of information and communications technologies at home; and

5) prevalence of bullying and lack of discipline in school.

“Philippine education system is treading on thin ice,” says PIDS. Per a 2022 World Bank report on global learning poverty, 9 in 10 Filipinos could not read and understand a simple age-appropriate text at age 10. “With the longest school closure among 122 countries and highly unequal access to the internet, digital education resources, and home support, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the situation,” says PIDS.

EdCom2 was a pet project of Sonny’s dad, the late Senate President Edgardo Angara, on reforming the Philippine educational system. In education, the earlier you educate kids, the better for them, the better for the country.

Poor quality of early childhood education

The No. 1 problem is poor quality of early childhood education.

Yes, pre-kinder and kindergarten enrolment is increasing—98% of 3 to 4 year-olds attend kinder schooling. But the dropout rate from kinder schooling is very high—60%.

Education, after all, is about quality, not numbers. In junior high school, the share of private school enrolment has fallen, from 50% in 1970-71 to less than 20% today.

Public schools are the problem

Public elementary and high school education is really the problem. About 90% of Filipino pupils are enrolled in public elementary schools; 80% of high school pupils are in public high schools. So the problem lies with the national government which runs these public schools. The government is not delivering quality education.

PIDS says early childhood education sector faces at least four challenges:

(1) Chronic malnutrition;

(2) The 20:1 ratio of children to child development workers reported in early childhood care and development, which is above the recommended ratios;

(3) 75% of the 3% who did not complete elementary schooling between school year (SY) 2018–2019 and SY 2019–2020 dropped out between kindergarten and Grade 4, of whom about 60% dropped out between kindergarten and Grade 1; and

(4) The need to articulate a framework for early childhood education and assess its quality.

“Stunting is the most bothersome among these challenges,” says PIDS. One in three Filipino children under five years old is stunted. We are among the top 10 countries in the world with the highest number of malnourished and stunted children.

The World Bank report is just the tip of the iceberg. In 2018, the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) showed only 1 out of 5 Filipino students achieved a minimum proficiency level in reading and mathematical literacies.

Moreover, the Filipino students’ average scores for both literacies were significantly lower than those of the member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

Observes the PIDS review: “The proficiency level of Filipino students across social class, rural and urban residence, gender, language at home, type of school, and early childhood attendance is dismally low.”

Students from private schools perform better on tests, but their share of enrolment is continuously dwindling.

For instance, the share of the private sector in junior high schools continuously declined from more than 50% in SY 1970–1971 to 20% in SY 2018–2019. Good luck Secretary Sonny.