By SEC. WILLIAM DAR – Department of Agriculture

Can we call the coconut industry a sleeping giant? Its potential to help fight poverty cannot be discounted. It is the third most dominant crop, after rice and corn. While the productivity of rice and corn has been steadily increasing, the country’s coconut farms need a shot in the arm.

Could we call the coconut industry a “sleeping giant”? Its potential to help fight poverty in the country cannot be discounted, as coconut is third most dominant crop behind rice and corn? But while the productivity of rice and corn farms has been gradually increasing, the country’s coconut farms need a shot in the arm.

The average yield of rice farms today is about 4 metric tons per hectare (MT/ha) from approximately 3.9 MT/ha in 2015. Meanwhile, corn yields increased from 2.91 MT/ha in 2016 to 3.1 MT/ha currently.

As for coconut, yields have remained at 40 to 45 nuts per tree annually, which is below the 200 to 300 nuts recorded in countries like India and Brazil.

So, I see hope in the drive of the Philippine Coconut Authority’s PCA), an agency under the DA, to plant hybrids that have the potential of yielding 150 nuts per year. The hybrids could also yield 300 nuts per year by augmenting hybrid technology with good agricultural practices (GAP).

But the coconut industry needs another market in the Philippines, which Republic Act (RA) 9367 or the “Biofuels Act of 2006” could provide.

RA 9367 provides for the increase in the coco methyl esther blend (CME) in diesel sold locally, which could result in billions of pesos in economic benefits for the industry.

A study conducted by the Asian Institute of Petroleum Studies Inc. (AIPSI) showed a 5% biodiesel requirement in the Philippines would need at least 360 million liters of CME per year. And to meet that requirement, about 489.8 million kilos of copra is needed.

If all diesel sold in the Philippines gets a 5% CME blend, that would result, based on the AIPSI study, to an import reduction in diesel imports by about 430 million liters a year. And with diesel-fed SUVs now the popular choice of affluent motorists, that figure could even be higher now, as the AIPSI study was made public by the PCA in May last year.

At present, the CME blend in locally-sold diesel is only 2%.

Environmental, social benefits

The AIPSI study also showed that biodiesel with 5% CME blend could reduce by as much as 83% the particulate emissions from diesel use, contributing to air pollution reduction. Furthermore, the study said the country spends as much as P16.4 billion a year to treat lung diseases and ailments, including cancer, which could be possibly reduced with the use of biodiesel with 5% CME blend.

The PCA estimated the total economic benefits in shifting to 5% biodiesel blend at about P110 billion per year, and I believe much of that could redound to the coconut farmer.

But the opposite view to increasing the CME blend in diesel is it would increase the cost of the fuel at the pump stations.

Nonetheless, the potential of increasing the biodiesel blend to 5% as stipulated by RA 9367 should never be overlooked, as its socio-economic and environmental impacts could also never be ignored. We also should consider that increasing the earnings of coconut household families would reduce migration towards the urban areas, which is a factor causing congestion and other social problems in cities.

Uncontrolled migration to urban areas could worsen traffic congestion, which in turn increases fuel consumption and worsens air pollution.

So, we should also take into account the social impact of increasing the biofuel blend for diesel over the long term.

Currently, copra prices are hovering from P20 to P25 per kilo nationwide, with the breakeven cost pegged at P15 per kilo. By opening up a new market for coconut farmers by increasing the biodiesel blend to 5%, copra prices should definitely improve.

And since the market for CME are petroleum firms, the potential for the big brother-small brother arrangement could be put in place, or organizing fragmented coconut farmers and assisting them to enter into mutually-beneficial arrangements with big millers or directly with petroleum firms. Such an arrangement should result in coconut farmers getting a fairer share in the economic benefits of increasing the biodiesel blend to 5%.

Industry’s position

In July this year, the Philippine Biodiesel Association (TPBA) proposed to increase the biodiesel blend to 5% by 2021, which I believe is doable and should be the way forward.

The United Coconut Association of the Philippines also said it was pushing for a 3% blend this year, 4% by 2020 and eventually, 5% by 2021.

Ironically, Malaysia and Indonesia have increased their biodiesel blend to 5% but using palm oil. Indonesia is even considering a 30% biodiesel blend, which is not surprising since it is currently expanding its lands planted to palm.

The move to a 10% palm oil blend for diesel sold in Thailand is also getting off the ground, a move that was made to absorb excess palm oil production.

As mentioned in the first part of this column-series, there is a European ban on palm oil stemming from environmental issues, with Indonesia’s burning of its forests to expand palm oil plantations under scrutiny. Perhaps this partly explains why there are moves to increase the palm oil blend for diesel among some Southeast Asian countries.

As for the Philippines, increasing the CME blend in diesel to 5% should also be viewed in the context of improving the lives of coconut farmers, of which a big percentage still belong to the “poorest of the poor.”

A ‘sleeping giant’

Along with the measures I mentioned in the first part of this column series like tapping the growing export market for coconut water and milk, intercropping in coconut farms, and planting hybrids in existing farms, I could even say the Philippine coconut industry is a “sleeping giant.”

Besides, coconut, mostly in oil form, is already one of the Philippines’ top 2 farm exports generating over $1 billion each year. Furthermore, coconut planting has not yet suffered the stigma of having a negative impact on the environment, and there are already numerous studies showing coconut water and oil are beneficial for human health.

And perhaps, CME-blended diesel will soon emerge as one of the best fuel for the vehicles, because of its potential impact on the environment through reduced particulate emissions.

So now is the time to awake the “sleeping giant” that is the coconut industry.

Coconut trees have been a common sight in the country’s rural areas. But alongside areas with many coconut trees are mostly communities where there is poverty and little progress.

And the coconut tree has been dubbed “The Tree of Life.” I find this ironic.

Ironic

Also ironic is while coconut products, primarily in oil form, generate more than $1 billion in export receipts annually, about 90% of the approximately 3.4 million coconut farmers still form part of the country’s “poorest of the poor.”

I could say at this point that the coconut industry’s potential has not been tapped because of low productivity from challenges like pest attacks, prevalence of typhoons, poor management practices and very low copra prices. And let me add that the local coconut industry has not yet capitalized on the growing demand for non-traditional products like coconut water and milk.

Coconut along with rice and corn dominate the Philippine agricultural landscape, with about 80% of lands devoted to farming planted to those three. While the yields of rice and corn are gradually increasing, those for coconut trees remain anemic and disappointing.

Currently, the average yield of coconut trees in the Philippines is 45 nuts per tree annually, which is below the 200 to 400 nuts per tree of countries like India and Brazil.

The only consolation is that the Philippines has vast lands planted to coconut, approximately 3.5 million hectares. India has 2.14 million hectares of land planted to coconut, but produces more nuts per tree than the Philippines.

According to the United Coconut Associations of the Philippines Inc., using 2014 figures, India produced 21.665 billion nuts, about 47% more than the Philippines’ 14.70 billion.

The good news is that it is possible to increase the productivity of coconut trees in the Philippines to 150 nuts per year using the hybrids developed by the Department of Agriculture-Philippine Coconut Authority (PCA).

Furthermore, a production level of 300 nuts per year could be achieved in well-managed plantations by augmenting hybrid technology with good agricultural practices.

But since it takes three to four years for hybrid coconut trees to bear nuts, interim measures are being pushed by the PCA like intercropping in current coconut lands to at least increase the earnings of coconut farmers.

Intercropping

So, under the Kaanib and Intercropping Program of the PCA, the agency is releasing livestock, poultry and seeds for short-gestation crops like vegetables to areas that are most affected by dropping copra prices. These include coconut farms that are farthest from milling facilities.

The PCA is also coordinating with the Department of Social Welfare and Development for the inclusion of farmers in the department’s aid/welfare programs like the cash for work and Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program or 4Ps.

Furthermore, there is a need to increase the incentives for the Participatory Coconut Planting Program (PCCP) from P40 to P85 per seedling.

Over the long-term, there is an urgent need to increase the lands planted to coconut, which the PCA will undertake in the next few years through programs like the PCCP. The PCA is also encouraging multilevel farming, where lands planted to other crops would also be planted to new hybrid coconuts.

Hybrids are still the best option for new coconut planting, as traditional tall varieties bear fruit in about seven years. Also, the yield of hybrids, as stated earlier, could reach 150 nuts per tree annually.

The industry needs new hybrid coconut trees, which will allow the country to take advantage on the European ban on palm oil stemming from environmental issues.

My message to PCA is this: Go full steam on increasing the number of hybrid coconut trees in the country!

Beyond copra

Today, most coconut farmers still rely largely on copra as their main or major income source. And since most coconut farmers are still fragmented or are disorganized, they have no power to command uniform or better prices for the commodity.

Meanwhile, billions of liters of coconut water are thrown away as farmers extract the coconut meat to produce copra, even as the world demand for coconut water is increasing by leaps and bounds.

According to the Philippine Statistics Authority, the Philippines exported $89 million worth of coconut water, totaling 63 million liters.

This is a small figure because according to studies by the Bureau of Agricultural Research (BAR) and the Philippine Center for Postharvest Development and Mechanization (PHilMech), both under the Agriculture department, the volume of coconut water that could be recovered in the Philippines is 2.4 billion liters annually.

The article “Agencies see vast potential for local coconut water production” published in The Manila Times on Jan. 18, 2019 showed BAR and PHilMech are undertaking a project to develop the technology and enterprise system and marketing for coconut water.

Also, the project is testing a locally developed village-level coconut water processing machine that could process 2,000 coconuts into 2,000 350-milliliter bottles per day.

According to University of Asia and the Pacific’s (UA&P) industry report The Coconut Industry: Local and Global Perspectives, coconut water is one of the fastest-growing beverage categories in the global market, increasing by 154% per year on volume and 159% per year on value during the past 10 years. So, what are we waiting for?

The UA&P report also said exports of coconut milk powder had been growing by 38% per year on volume, with countries like The Netherlands, Japan, the United States, France and Australia as the major markets. Again, what are we waiting for?

I must emphasize, however, that as the exports for non-traditional coconut products like coconut water and powder increases, there is a need for poor farmers to also enjoy the fruits of the harvest, or for them to earn more by including them in the value chain.

Also, major agribusiness companies entering into mutually beneficial agreements with coconut cooperatives under the “big brother-small brother” arrangement would help lift millions of poor coconut farmers out of poverty.

In the next installment of this series, I will discuss, among others, the potential of increasing the coco methyl ester blend in fuel in accordance with Republic Act 9367, or the “Biofuels Act of 2006,” in leveling up the country’s coconut industry.

Coconut industrya sick man

While coconut is one of the two agricultural commodities that earn the country more than a billion dollars in export revenues every year. Yet its vast potential to earn even more has never been tapped because of numerous issues bugging the industry.

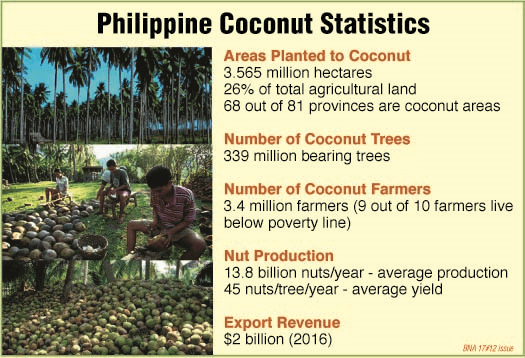

The area currently planted to coconut is about 3.565 million hectares or 26% of country’s total agricultural lands. Also, 68 out of 81 provinces are coconut-growing areas. At present, these lands host about 339 million bearing coconut trees and 3.4 million farmers who, ironically, live mostly below the poverty line even as coconut exports reached $2 billion in 2016.

Nut production on the average was 13.8 million or 46 nuts per tree per year.

Although coconut exports, primarily from processed products like oil, are expected to rise, the vast potential of the coconut industry has yet to be tapped and measures have to be put into place to include the poor farmers of the crop to earn more.

The bugs

So what bugs the local coconut industry?

Besides low yield per tree and aging trees, the supply chain is largely unorganized and made up to dispersed small holdings that affects economies of scale in input supply, primary processing and marketing.

The small production lots and high transport translate to high cost of logistics, which affect both farmers and processors.

Market threats

In the global scene, there are market threats from tariff and non-tariff barriers such as minimum residue levels and labeling regulations.

Addressing low yields at the farm level can be an excellent move to helping realize the coconut industry’s potential as a bigger generator of export dollars.

Obviously, the low yields are caused by poor genetics, nil fertilization, and limited replanting of tree stocks. Also 20% of coconut trees are already senile while most trees are planted in marginal lands that also affect yield. Meanwhile, large lands planted to the crop have low genetic potential.

I actually find the 46 nuts per tree/year yield to be ridiculously low considering that in India, the average is 250 nuts, Mexico 300 nuts and Brazil 400 nuts.

I recommend ramping up research and development (R&D) efforts to improve the productivity of coconut lands; in short, we need science-based solutions.

What R&D must focus on

R&D efforts on coconut must address low productivity, pests and diseases, the establishment of post-harvest and processing facilities, value addition, crop diversification (crops and livestock integration), and soil mapping.

Alongside R&D efforts is the establishment of infrastructure and other logistics that include processing centers, other post- harvest facilities, farm-to-market roads and irrigation.

Also, the power of ICT can be harnessed to improve production and delivery systems.

Then agribusiness development should be pursued, which will also include provision for credit and other risk management tools (like insurance and subsidy), so farmers and processors can pursue innovations that have potentials to improve the coconut industry.