Murders during Duterte’s time as mayor and the early part of his presidency target of unprecedented investigation; killing of 204 victims to be looked into

On the heels of the Senate investigation into the alleged overpricing and cronyism involving a Chinese company, Pharmally Pharmaceuticals, Rodrigo Duterte faces an equally formidable challenge during his last year as president.

This is the investigation by the Hague-based International Criminal Court (ICC) into alleged human rights violations during his War on Drugs (WoD) as mayor of Davao for 23 years and during the early part of his presidency, from June 30, 2016 until March 19, 2019.

The killings earned for the grizzled Davao leader the monickers, Duterte Harry or “The Punisher”.

Corruption and illegal drugs killings could impact of Duterte’s political future. In the past, most presidents were fallen by the issue of corruption and cronyism. No president has been defeated for alleged human rights violations. Corruption is the unmaking of nearly all Philippine presidents.

Sept. 15, 2021, the Pre-Trial Chamber I of the International Criminal Court granted Prosecutor Fatuou Bom Bensuoda’s request to commence an investigation in relation to crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court allegedly committed on the territory of the Philippines between Nov. 1, 2011 and March 16, 2019 in the context of the so-called ‘war on drugs’ campaign.

On June 14, 2021, the prosecutor, a Fatou Bensouda, Gambian woman criminal law lawyer, filed a public but redacted version of the request to open an investigation, initially submitted on May 24, 2021, requesting authorization to commence an investigation into the Situation in the Philippines, as provided for in Article 15(3) of the Rome Statute.

Pre-Trial Chamber I composed of Judge Péter Kovács, Presiding Judge, Judge Reine Adélaïde Sophie Alapini-Gansou and Judge María del Socorro Flores Liera, examined the Prosecutor’s request and supporting material. The Chamber also considered 204 victims’ representations received pursuant to Article 15(3) of the Statute.

On Aug. 29, the ICC reported that 94% of the 204 representations filed before the court supported a formal investigation of the crimes committed in the president’s anti-drug campaign.

The 204 submissions represented 1,050 families acting on behalf of 1,530 drug war victims, according to human rights lawyer Kristina Conti.

Reasonable basis to begin probe

In accordance with Article 15(4) of the Statute, the Chamber found that there is a reasonable basis to proceed with an investigation.

In particular, the ICC noted that specific legal element of the crime against humanity of murder under Article 7(1)(a) of the Statute has been met with respect to the killings committed throughout the Philippines between July 1, 2016 and March 16, 2019 in the context of the so-called ‘war on drugs’ campaign, as well as with respect to the killings in the Davao area between Nov. 1, 2011 and June 30, 2016.

The Chamber stressed that, based on the facts as they emerge at the present stage and subject to proper investigation and further analysis, the so-called ‘war on drugs’ campaign cannot be seen as a legitimate law enforcement operation, and the killings neither as legitimate nor as mere excesses in an otherwise legitimate operation.

Widespread and systematic attack

Rather, said the ICC statement, the available material indicates, to the required standard, that a widespread and systematic attack against the civilian population took place.

The Philippines withdrew from the Rome Statute recognizing ICC and is proceedings on March 17, 2018.

Jurisdiction retained

While the Philippines’ withdrawal from the Statute took effect on March 17, 2019, the Court retains jurisdiction with respect to alleged crimes that occurred on the territory of the Philippines while it was a State Party, from Nov. 1, 2011 up to March 16, 2019.

In July, our Supreme Court ruled unanimously that Duterte could not invoke the Philippines’ withdrawal from the Rome Statute to evade investigation by the ICC prosecutor.

The Supreme Court declared that the Philippines was bound to recognize the jurisdiction of the ICC and cooperate with its processes even after its withdrawal from the Rome treaty.

Families heard

In its report last month, the ICC said almost all the families that accused the president of instigating the killings wanted accountability and justice.

The ICC report noted other crimes against humanity committed in the drug war: murder, torture, imprisonment, disappearance, attempted murder, and sexual violence.

7,000 killings

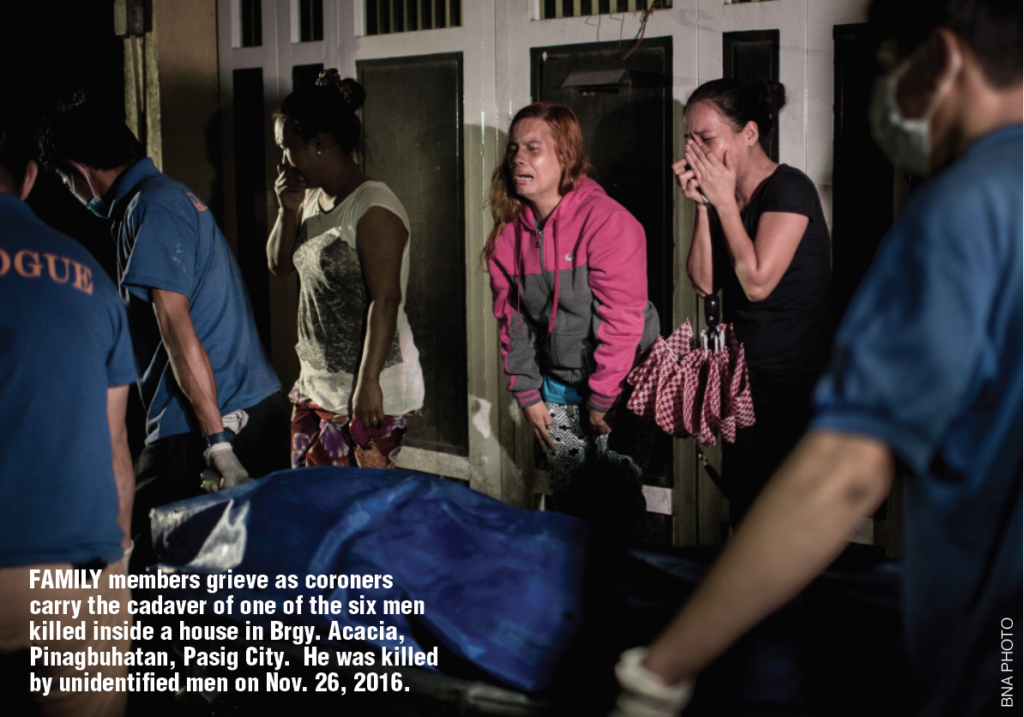

The government had acknowledged about 7,000 killings during Duterte’s presidency.

ICC cites local and international human rights groups to claim real figure was 12,000 to 30,000, including killings by state-backed vigilantes.

In the Sept. 15, 2021 ruling, the ICC judges approved the request by their prosecutor Bensouda to begin the investigation into potential murder as a crime against humanity.

Their assessment of material presented by prosecutors, who had asked for permission to investigate, was that “the so-called ‘war on drugs’ campaign cannot be seen as a legitimate law enforcement operation,” but rather amounted to a systematic attack on civilians.

Per ICC documents, in 2015, the Dangerous Drugs Board (“DDB”), the body tasked with defining the Philippines’ policy and strategy on drug abuse prevention and control, commissioned a nationwide survey which estimated that there were 1.8 million drug users in the Philippines, a figure cited by the government of the Philippines as the official number of drug users.

Millions of addicts

In his public speeches, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has frequently inflated this number, claiming variously that there are “three million” and “four million addicts” in the Philippines.

From as early as February 2016 and throughout the War on Drugs (WoD), the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (“PDEA”) repeatedly reported that a high proportion of the country’s barangays were “drug affected” – meaning that a drug user, dealer (or “pusher”), manufacturer, marijuana cultivator, or other drug personality had been “proven” to exist in such locations – and indicated that the WoD should continue until all barangays could be considered cleared.

According to the DDB, the most-used drugs in the Philippines are methamphetamine hydrochloride (commonly known as “shabu”) and cannabis (marijuana).

Duterte Harry, “The Punisher”

During 1988-1998, 2001-2010, and 2013-2016, according to ICC documents, Duterte served as mayor of Davao City.

Throughout his tenure as mayor, a central focus of his efforts was fighting crime and drug use, earning him the nicknames “The Punisher” occasions, Duterte publicly supported and encouraged the killing of petty criminals and drug dealers in Davao City.

During Duterte’s tenure as mayor, Davao City police officers and the so-called “Davao Death Squad” (“DDS”), a vigilante group comprising both civilian and police members linked to the local administration, allegedly carried out at least 1,000 killings.

Those killings share a number of common features including the victim profile, advance warning to the victim, perpetrator’s profile, the means used, and the locations of incidents.

In 2016 and 2017, two men, including a retired police officer, claimed during Philippine Senate hearings to have been part of the DDS and to have been ordered and financed by then-Mayor Duterte to carry out extrajudicial killings of suspected criminals and drug personalities.

In 2016, Duterte ran for president. His platform centered on promises to launch a war on crime and drugs, by replicating the strategies he implemented during his time as Davao mayor.

As president, Duterte launched Project Double Barrel. It had two basic components.

The first, Operation Tokhang (or “Oplan Tokhang”, meaning operation “knock and plead”), focused on house-to-house visits, carried out to “persuade suspected illegal drug personalities to stop their illegal drug activities.

The second, Operation High Value Target focused on various types of operations targeting high-value and street-level targets involved in trafficking and selling illegal drugs, such as so-called “buy-bust” operations (a form of sting operation), serving search and arrest warrants, carrying out raids, and setting up checkpoints.

Although these two components changed in some respects over time, they remained at the center of the Philippine National Police’s WoD strategy throughout the period covered by the ICC prosecutor’s request.