By Jullie Yap Daza

From her book, “Chinatown Is Not A Place”

The Chinese love food as much as Filipinos do. Put the Chinese standard lauriat side by side with the fiesta culture of Filipinos, and what’s not to like if you’re Chinoy? Love lauriat, love fiestas, love National Food Month, love being food-obsessed (a New York Times observation).

If the Chinese did not love food, why would they dine on 14-course meals set on a round table? Those tables have grown in size, perhaps in keeping with the expanding menus. Even before the first decade of the 21st century could settle in the collective tummies and memories of mainland and overseas Chinese, the affluent classes in China’s big cities were already sitting around tables set for 22 or 24.

That size is now the norm in a few of the opulent restaurants in Metro Manila’s swankiest hotels to accommodate gourmets, connoisseurs, Chinese and other tourists, especially the ones who frequent the most lavish of the resort hotels and casinos.

Democratic base

What’s curious about Chinese restaurants is their wide democratic base. They can be as cheap and poor-looking as they can be the stuff of the dreams of emperors with their dragons and phoenixes in jade, marble, coral.

Taking advantage of an appetite-inducing versatility of means and menus, eating clubs have been springing up to indulge the taste for adventure among Chinese, Filipinos, any and all food trippers.

Our little eating club once took an old friend on a food trip to Chinatown. After an absence of something like 10 years, this homecoming treat, or so we thought, would jolt him with either a wave of nostalgia or the kind of culture shock that he deserved for having stayed away for so long.

Nostalgia, because the restaurant has not changed its menu in the last century and a quarter? Culture shock, because the restaurant still looks the same, not having been refreshed with new paint, new floor tiles, not even a brand-new comfort room, after all these years? Only the service staff looked different, or was that because the old ones had been sent off to pasture?

No sooner had we found a table on the mezzanine—no reservations required in this dump, as our continental-mannered guest would say later—than he began fidgeting nervously. Was he looking for cockroaches on the floor (it was stained with oil dribblings) and spiders on the wall?

The paper napkins were six-inch squares, of the cheapest kind available by the crate in Ylaya or Juan Luna, not anything like the linen napkins he would have been used to in Paris and London, certainly they were not soft enough to dab at his lips.

The waitress arrived at our unstable table (one leg apparently shorter than the other three). She was garbed in a hollering shade of fire-engine red mixed with over-ripe mango yellow and she carried a metallic tray loaded with plastic bowls and plates, followed closely by the busboy gingerly holding an obese kettle of hot tea—a kettle large enough to be described as military-size. Which beast could drink tea poured from such an obese, obscene container?

Was this the way to honor a gentleman home from some sophisticated post in civilized Europe? We were not thinking, we were busy digging into our noodles with our plastic chopsticks—how utterly gross!—while our guest struggled with his disposable ones (for hygienic purposes, you know the drill) until he gave up and asked the waitress for spoon and fork, no knife necessary, he didn’t believe in cutting his noodles. Aha, at least he remembered one of those Chinatown superstitions.

I could’ve offered him some words of comfort but was afraid to, imagining his stomach churning like a storm over the Pacific before hitting land. There was more to come, more dishes, more agony.

The soup was more of a stew, a thickly brown paste-like sauce that regular patrons of the restaurant are said to relish without ever wanting to find out its ingredients. If our guest had asked me what was in the soup-like stew or stew-like soup, I would’ve told him ignorance is bliss, leave the mystery to the chef, er, I mean cook.

Chinatown has not changed much

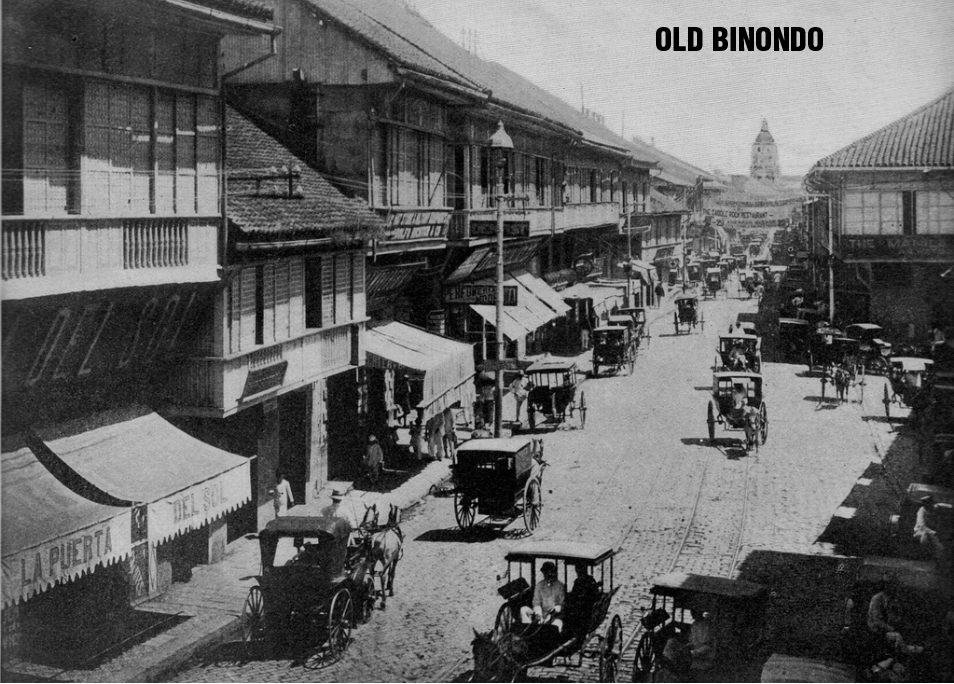

I’m digging up this story from my recent past to show how the old Chinatown has not changed much (except the prices). Change has not altered the most familiar landmarks, now distinguished by age rather than stature. The big change that has come is that it is no longer just yesterday’s Binondo Chinatown.

High-rise condominiums tower over a stagnant estero. Horse-drawn calesas will not yield to wide-bodied SUVs (‘tis said these are better at fighting off kidnappers). A maze of little shops with one or two shopkeepers continue the customary “small business” look of modesty and unobtrusive service, better to lie low and avoid the hot eyes of intruders with a hostile agenda.

Not far from Ongpin, Binondo, and long before World War II, a generation of Chinese tradesmen were already thriving in their chosen trades in Intramuros, the Walled City, part of which was the ghetto-like Parian where the comings and goings if its resident aliens were restricted.

A charming footnote in Intramuros of Memory by Dr. Jaime C. Laya and Esperanza Gatbonton lists the merchants in “An Intramuros Address Book” from Rosenstock’s Manila City Directory of 1919, categorizing them by trade, ownership, and street. The book lists the following obviously Chinese traders:

• Dressmakers – Ah Cheong, 225 General Luna; Wah Sing, 184 Real.

• Dry goods retail – Lee Pan Sui, 116 Real.

• Japanese and Chinese goods – Nagasaki Bazaar, 153-155 Real.

• Tailors, Merchants – A. Pong, 120-122 Real; Ah Wan, 72-74 Real; Lam Lee, 126

• Real; Tack Hing, 264 General Luna; W. Ning, 82-84 Real.

In the Intramuros of the era of Rodrigo Roa Duterte — “My grandfather was Chinese” — Chinese-Filipino entrepreneurs carry on the mercantile tradition. Mayhap Intramuros was the first commercial Chinatown?

Case in point, Leonard Tsai’s fittingly named mini-mall, Intramall at 706 Escueta Street, well within earshot of those long-ago Chinese shops on Real and General Luna.

Intramall’s main line, cotton undershirts tagged with the long established name of Guitar, a brand familiar to generations of Chinese and Filipinos and sold retail or wholesale, shares the spotlight with a snack bar on the mezzanine where office workers, seamen, and university students take a break for milk tea, a Taiwanese invention, or so we’ve been told.

The small mall’s neighbors are Manila Cathedral, San Agustin Church, Kaisa-Angelo King Heritage Center with its Bahay Tsinoy Museum, Manila Bulletin Bldg. of the Yap family, Fort Santiago, Destileria Limtuaco Museum, and the headquarters of the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines, whose three-story building once housed the Immaculate Conception Academy for Chinese Catholic girls until the ‘60s, when the school initiated the push of “Chinatown” to Greenhills in the City of San Juan.

Of more recent vintage in the same Intramuros neighborhood is a full-service restaurant managed by a Chinese-born Catholic lay leader and philanthropist, Elvira Go-Yap, whose family is in the sweet business of candy manufacturing. Elvira’s Ristorante delle Mitre stands directly in front of the entrance to San Agustin church, and is popular for its bishop-inspired dishes culled from family cookbooks.

As the Chinoy population has been growing in size and so-called Westernization, and in keeping with their enriched lifestyles and enhanced socioeconomic status, Chinatown has outlived the Ongpin-Dasmariñas-Nueva grid, although Divisoria remains a mecca for bargain hunters from all over the islands.

A stretch of highways away, Ortigas Ave. and Epifanio delos Santos Ave., there’s a younger Chinatown that has been on the upswing since the ‘70s and continues to grow to match its towering high-rises. New Manila is its official address but the name is not complete without the “Greenhills Chinatown” tag. According to a teenaged Chinita coed, “My rich classmates all live in New Manila.”

In a sociocultural sense, New Manila is not limited to the Broadway-Gilmore-Hemady area; it goes well beyond the City of San Juan, reaching the sprawl of villages echoing in their names the green and hills of Greenhills, the likes of Corinthian Gardens, Corinthian Hills, Valle Verde, and Greenmeadows, the vicinity crowned by the elegant white church of the Mormons.

Belly of the dragon

Taken as a whole, this vast neighborhood favored by Chinoys as well as Filipinos is where the belly of the dragon supposedly resides. Come to think of it, Greenhills and its cousins could not have been more aptly named. Green is said to be a prosperous color, as in the green of American dollars, and Hills stands for a gently rolling terrain indicative of good feng shui.

Francis Chua, chairman emeritus of Philippine Chamber of Commerce and Industry and chairman of Philippine Silk Road International Corp., has his own off-the-cuff explanation for Greenhills coming into prosperity: “Many families moved there because of ICA, Immaculate Conception Academy, and Xavier School,” the two schools favored by the affluent Chinese for the education of their heirs and heiresses.

As families grew, so did the need for commerce to service their hour-by-hour, day-to-day needs—banks, supermarkets, shops, restaurants, entertainment, parking buildings to keep up with the ever increasing car population.

On any given day as long as it’s not a bank holiday, the neighborhood is awash in cash flowing in and out of a parade of banks and their multiple branches in Greenhills, Metrobank, founded by George S.K. Ty, has seven branches. Banco de Oro of Tessie Sy-Coson boasts nearly a dozen. In Annapolis, Connecticut, Missouri, D Square, Roosevelt behind ICA and Mary the Queen church, which are two big buildings considered as one branch; Greenhills West in Limketkai Bldg., Ortigas Ave., Wilson, Greenhills North, Greenhills Shopping Center.

Taken as one entity, this grid of streets spells the prosperity of Greenhills in the language of currency, cash, commerce. Prior to the rise of Greenhills Chinatown, the original Binondo Chinatown was the logical site for operating the “Binondo Central Bank” during a foreign currency-strapped episode of Martial Law. Most, if not all, of those banks are still around, sound as ever, busy as usual.

Dynamic work in progress

Commerce is eternal, like Chinatown, a dynamic work in progress that has not reached its full potential yet — factor in the rapid growth of technology and the government’s tilt toward China as a BFF — for as long as Chinoys, Chinese-Filipino mestizos, and Chinese-Chinese (in the vernacular, Chinese na Chinese, i.e. Chinese to the core, unadulterated) evolve, move, develop in their desired directions. Living down or living up to its reputation as the world’s oldest, Chinatown Sr. is where the head of the dragon resides, its place in history thus assured.

Amid the hustle and bustle of banking, shopping, going into and out of Greenhills Jr.’s Catholic churches and elitist schools (besides ICA, Xavier, La Salle), New Manila has found a tranquil spot for Buddhists. The Buddhist Wisdom Park, built by Mariano Yupitun, faces the Church of Our Lady of Carmel, injecting an ecumenical air of calm and prayerfulness in a residential neighborhood lined with mango trees whose fruits are awaited by streets urchins.

Whether the fruits fall according to the season or the law of gravity or they are picked by hand or an improvised rod, traffic on Broadway St. is moderate on working days and, ironically, builds up on Saturday, a going-out day for young and older as the weekend kicks in. Cross Broadway on N. Domingo and you’re on your way to Ortigas for Greenhills.

The street is chockful of computer shops, snack and grocery stores (including a favorite stop for Filipino housewives who have cultivated a taste for ma’chang, siopao, sweets from preserved plums and dates, fresh lumpia, sausages, etc.)

The Buddhists who visit Wisdom Park on Broadway would be more interested in the teachings of Buddha than in the taste of Chinese delicacies. Accordingly, they meet regularly to listen to talks and lectures on philosophy, not only as it pertains to the Buddhist reverence for life, Buddhism not a religion but a way of life.

They take up their seats in spacious classrooms that allow them a view of the foliage of a pair of big fat trees providing shade and dappled shadows. The larger tree is a boddhi (or bo) from Sri Lanka, a great-great-grandchild of the tree under which Sakya Muni, or Buddha, sat and gained enlightenment.

Underground in the meditation room, meditators sit on a glass floor drawn with a giant lotus blossom at its center. The glass tiles are lighted from underneath, so the feeling of floating above a lotus pond is a bonus for those who have the imagination to level up in a levitation-like mood.

On certain days vegetarian meals are served in the canteen, although the uninitiate visiting for the first time might consider as the highlight of their tour a walk under the pair of bo trees facing each other in the garden. You walk, literally in circles, seven times under each tree, to ask for a favor or pray for healing or for special intentions for a loved one.

Like Catholics who petition God or the saints or the Blessed Mother in the church across the road, this Buddhist park does not label itself a temple. There are Buddhist temples in Metro Manila and outside the National Capital Region, for the devout as well as the curious.

A temple visit

I remember the many times I accompanied my “Lola Small Feet” on her temple visits, her favorite being the one in Narra at the back of Recto Ave. in Divisoria. She had delicate bound feet, but she was tall and elegant, and she taught me how to bow, pray with hands clasped under my chin in the pai-pai (praying) position, the same position when I’m praying in a Catholic church.

Grandma and I, we offered gifts of flowers and soft fluffy cakes, no icing, on those special days when a deity celebrated his birthday and expected humanity to recognize their importance in the lives of mortals.

On one such occasion, which I remember very well and will not forget until the day I’m canonized for my ecumenicity, the Buddhist nun who greeted Grandma caught me putting my nose to the spray of flowers that I carried in my childish arms.

The nun glared at me and admonished me sternly, like a principal or a priest: “Do not smell the flowers if they are for the altar! Would you give someone a piece of candy after tasting it first?” And that, as far as I was concerned, was Buddhist commandment No. 1.

Chinatown is more than geography. Chinatown is not a place; it is more than one place. Binondo to Greenhills, the Chinatown of old or Greenhills the new Chinatown, it’s a way of life, a blending of cultures and people where memory, imagination and the future intersect.